WASHINGTON (March 3, 2022)—Republican lawmakers in the Maryland state legislature are fighting the Democrats' newly-proposed congressional districts, drawn to make it nearly impossible for a GOP candidate to win in all but one seat.

In Kentucky, Democratic lawmakers are challenging Republican-favored congressional maps in state circuit court.

In Ohio, Republicans have crafted a redistricting plan favoring their party in at least 10 of 15 House districts. Now it's up to the Ohio Supreme Court to decide whether the state GOP violated the state's constitutional prohibition against gerrymandering.

"The map news of late is showing to me that our process is quite chaotic and almost kind of arbitrary," said Ned Foley, who directs Ohio State University's election law program.

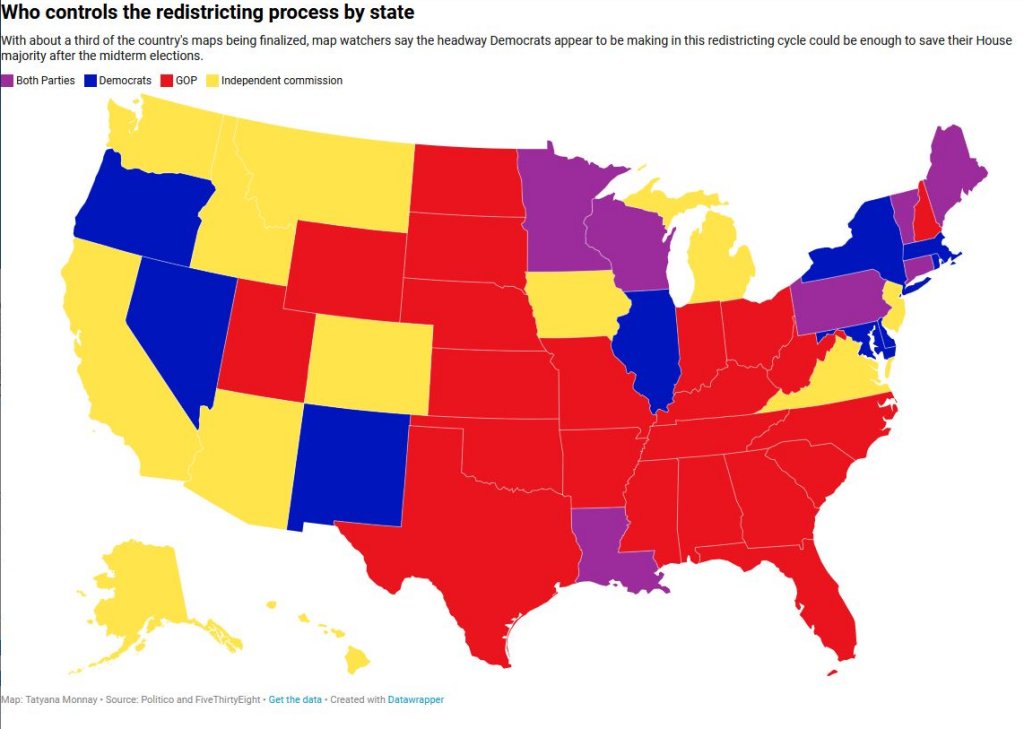

All across the country, states are drawing new congressional district lines ahead of the November midterm elections. Each state is playing by its own rules. And advocates say reforms are long overdue.

Some states allow the political parties to draw district maps—and many end up in court challenges by the parties that think they would lose seats. Other states have independent, non-partisan commissions.

On Monday, the Supreme Court denied a GOP request to block redistricting maps in North Carolina and Pennsylvania, where lower courts have approved them. Despite dire warnings ahead of this cycle that Republican-controlled state legislatures would produce new maps that would put Democrats at a disadvantage, the results apparently haven't quite worked out that way.

After the Supreme Court's decision on North Carolina and Pennsylvania, David Wasserman, House editor of the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, tweeted: "This ruling ensures the 2022 House map will be much less skewed towards Republicans than the current one (and perhaps not skewed towards Rs at all)."

But Foley told Capital News Service that the system is broken.

"If you think about redistricting as the first step in the process of democracy and self-government that you have to do every 10 years because of the new census and population shifts, you'd like to think that it could be more orderly and more rational," he said.

Although some lawmakers have tried to address gerrymandering since the 1980s, Congress has not passed federal redistricting reform that would end partisan map manipulations and the lawsuits that inevitably follow.

"It's really important that our policymakers recognize where things stand because democracy is a very fragile thing," said Yurij Rudensky, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice in New York. "And it's under unprecedented strain right now and it's clear who is being targeted and what the stakes are."

Congressional elections are less competitive after Republicans drew in advantages for the GOP during the 2010 redistricting cycle. Votes don't always determine an election since some districts are now exclusively safe for Republicans or Democrats, depending on the state.

The once-in-a-decade redistricting process is considered by many observers as a free-for-all in which districts are carefully revised to benefit whichever party is in control of the state legislature.

This isn't a new phenomenon. Drawing congressional maps to benefit a political party, also known as gerrymandering, has been around since the birth of the United States.

"Both parties are executing their strategies," Adam Kincaid, executive director of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, told CBS News. "We've been saying all along, we're just taking seats off the board and going on offense where possible. And they've been doing the same."

The National Democratic Redistricting Committee says its strategy protects communities of color, which are targets of GOP map-drawers.

"In state after state, Democrats are drawing maps that reflect the population trends in the census," Brooke Lillard, deputy communications director for the Democrats' redistricting arm, said in an email.

"The will of the voters be damned—that's the Republican approach," she said.

In Maryland, the Republicans are upset over district maps that they say are drawn to favor Democrats.

Seven of the state's eight House seats are held by Democrats and the maps that would govern the next 10 years would not change that. In fact, the new districts would make the one held by the only Republican, Rep. Andy Harris, more competitive.

Two lawsuits challenging the maps currently are moving through the Anne Arundel Circuit Court.

Nationwide, both parties are intensifying their efforts to gain advantage.

They have created groups such as the National Republican Redistricting Trust and the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, to support redistricting goals and strategies.

Groups like the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee have raised millions to prep state legislatures. "Dark money" groups that don't disclose their donors have poured thousands of dollars into efforts to influence map drawing this cycle, OpenSecrets reported.

But advocates for reform say the gerrymandering that maps are undergoing this cycle is the worst they've seen.

"It's in this moment where we are seeing unprecedented assaults, incredibly aggressive gerrymandering that are targeting communities of color," Rudensky said.

In the 1980s, Republicans including now-Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Kentucky, led the redistricting reform effort in Congress. Back then, the GOP was struggling to get more House seats. Today, it's Democrats on the Hill pushing for reform and wanting to carve out more power for the next decade.

"It's the ones with the power (who) don't want to give it up," said Sara Sadhwani, an associate political science professor at Pomona College in California.

Rep. Jim Cooper, D-Tennessee, thinks passing reforms would be difficult in any Congress.

"The dirty secret is that both parties love gerrymandering if they're on top," Cooper told CNS. "They hate it when they're on the bottom."

A veteran of 32 years in the House, Cooper is retiring because Tennessee Republicans sliced his Nashville district into three pieces.

The next push for reform should be an individual bill to avoid what happened with a comprehensive election and voting reform measure called the For the People Act, Foley said.

Partisan gerrymandering would have been banned in the For the People Act. But the overall bill stalled in the Senate because Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona did not back it.

The push for a compromise bill—partly led by Manchin—included reform that gave states more choice in what redistricting process they implement. But that approach was blocked by Senate Republicans.

Cooper, who introduced reform that would require states to use independent commissions to redraw maps, said it's difficult to find even one Republican to support federal redistricting reform. No Republicans in the House co-sponsored Cooper's bill.

"Find me a live Republican who's willing to do this," Cooper said. "They are very good at party unity. It's going to be really hard to find one willing to (stray from the party line). They rarely do that sort of thing."

Some point to state courts and ballot initiatives to fill in gaps that federal reform would address, but it's still not enough, according to Sadhwani.

"It really comes down to whether or not the people can have a say," said Sadhwani, who was on California's independent commission this cycle. "Not all states even allow ballot measures. So it's a pipe dream in many places, unless there's federal action."

Rudensky said that regardless of current safeguards like state court litigation and ballot measures some states have instituted in the redistricting process, Congress still needs to provide some kind of national standards when it comes to how states draw new lines.

And without guidance from Congress, relying on the courts can be a problematic strategy, Foley said.

Courts can allow bad maps to get through, Rudensky said, using Alabama's latest map developments as an example.

Last month, the Supreme Court's 5-4 ruling reinstated disputed maps that were challenged for disenfranchising voters of color in Alabama for this year's election.

But the Supreme Court can't step in on cases of partisan gerrymandering. The court gave up the legal authority to rule on cases of partisan gerrymandering after a 2019 ruling involving Republicans in North Carolina and Democrats in Maryland.

However, the high court still does hear cases involving racial gerrymandering, which could potentially violate the Voting Rights Act.

Most of those advocating reform believe each state should have an independent, non-partisan commission to draw new district lines and take map-drawing power away from political parties.

There is a connection between more fair, competitive maps and the independent commissions that draw them, said Chris Warshaw, an expert on redistricting who teaches political science at The George Washington University in the nation's capital.

"Even states that are otherwise controlled by Republicans, you don't see a big Republican skew in the map if there's a nonpartisan commission," Warshaw said.

Federal redistricting guidance will further support the principles of democracy, Rudensky said.

"It is critical to revamp the systems to create new safeguards," Rudensky said. "There's quite literally just nothing more important than ensuring that the public has full faith and trust and connection to our government, which is, of course, supposed to be a representative one where all communities are able to secure their fair share of political influence and of resources."

With House seats up for grabs, calls for redistricting reform grow louder