Ask him, and Stanley Mitchell will proudly tell you he works 12 hour days.

Over the last seven years, the 71-year-old Charles County resident has held a sweeping assortment of jobs, sometimes juggling multiple at the same time. It's a big change after spending close to 40 years ping-ponging around the Maryland prison system, serving time for driving the getaway car in a homicide—a charge he denies to this day.

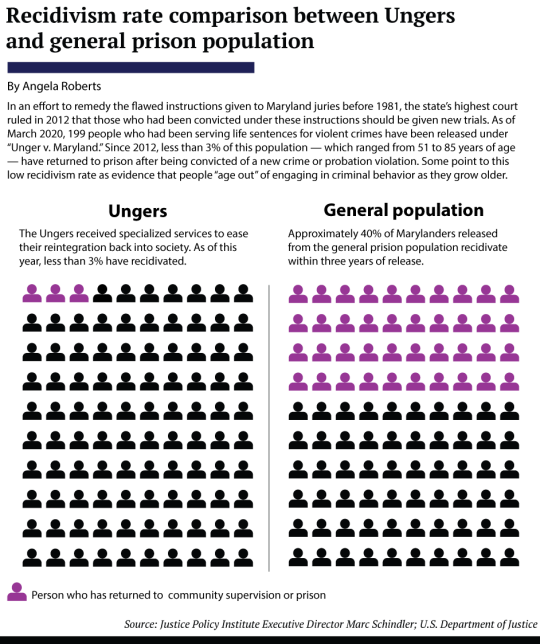

Mitchell is one of 199 people serving life sentences for violent crimes to have been released on probation since 2012, when Maryland's highest court ruled them entitled to a new trial in an effort to remedy the flawed instructions given to the juries that convicted them. At the time of their release, members of this group ranged from 51 to 85 years old and had spent an average of 39 years behind bars.

Since coming home, the "Ungers"—nicknamed after the case under which they were released, Unger v. Maryland—have gotten married, found jobs, reconnected with relatives and become mentors in their communities. As of March of this year, only five have returned to prison after being convicted of a new crime or probation violation.

Criminal justice reform advocates in Maryland say this low recidivism rate exemplifies what research has shown for decades: as people grow older, they "age out" of engaging in criminal behavior. Keeping this high-needs population locked up, they argue, needlessly drains away taxpayer money and, as one advocate put it, turns prisons into "extraordinarily expensive nursing homes."

Today, even as prison populations are falling nationwide, the number of incarcerated people considered to be geriatric is quickly expanding—riding on the wave of "tough on crime" sentencing practices that began proliferating in the 1980s. One report predicted that by 2030, people over 50 will make up one-third of the U.S. prison population.

For the last few years, an entourage of activists, state legislators, public defenders and policy experts have been working to ease the doors open to a parole process that many say is now stifled by politics.

By and large, they have the same goal: to give an aging population a better shot at coming home.

"Just locking people up does not solve all ills," said Del. Kathleen Dumais, who has been active in efforts to tamp down mass incarceration in Maryland.

TAKING STEPS TOWARD REFORM

In Maryland, the geriatric release program aims to give incarcerated individuals who are 60 years and older, and otherwise eligible for parole, a potential path to freedom.

However, despite the best attempts of state lawmakers to expand the program back in 2016, it remains strikingly under-used.

In 2018, Becky Feldman, the state's deputy public defender, started looking into just how many people were eligible for release under the program. Out of the entire incarcerated population in Maryland, she came up with just one person: a 62-year-old man she eventually helped get paroled.

She marked down what she observed in a memo to Daniel Long, a retired judge who chairs a board established to monitor the success of the Justice Reinvestment Act, a massive criminal justice reform bill passed in 2016. Long convened a workgroup to take another crack at expanding geriatric release and after four months of work, the group presented its final recommendations to the board.

Among other reforms, the recommendations called for the program's eligibility criteria to be extended to those serving time for nonviolent offenses. According to the workgroup, if all of the recommendations were implemented, the number of people eligible for geriatric release would jump to 265 individuals—a population only expected to increase over time.

But even though the recommendations were pitched as a "pilot program" with the potential for further expansion, Justice Policy Institute executive director Marc Schindler and other criminal justice reform advocates criticized them as not being far reaching enough—despite the success of those released under the Unger decision, they excluded those who were sentenced to life.

Schindler remembered the reactions of a group of men serving life sentences in the Jessup Correctional Institute when they were told that they had been excluded from the workgroup's recommendations. They were devastated, he said, and were hardly pacified by the possibility that they might be included in a future iteration of the program's expansion.

"'I don't have too much longer,'" Schindler recalled some of the men saying.

THE LEGISLATIVE FIGHT

Since getting out of prison seven years ago, Mitchell says he's avoided trouble.

"Besides red light cameras, I haven't had any negative interactions with law enforcement at all," he said.

Same goes for the vast majority of the Ungers—all of whom, like Mitchell, were serving life sentences for violent offenses. And just like Mitchell, many were recommended for release by the Maryland Parole Commission over the course of their time behind bars. Still, they didn't walk free until becoming eligible to receive new trials in 2012.

That's because Maryland is one of just three states in the country where the governor gets final say on whether a person in prison on a life sentence should get out. And ever since Gov. Parris Glendening announced in 1995 that "life means life"—refusing to grant parole for people serving life terms except for medical reasons—it's been a decision that's rarely handed down.

Even though Gov. Larry Hogan's actions have represented a departure from those of previous administrations—he has paroled or allowed the parole of 21 individuals serving life sentences, commuted the sentences of 21 and released another four on medical parole—some still say the governor's inclusion in the parole process leaves it needlessly warped by politics.

This year, the Maryland General Assembly heard two bills that would remove the governor from the parole process, but in the midst of the rapidly spreading coronavirus outbreak, state lawmakers ended the session in a rushed whirlwind, passing over 650 bills in just three days. Neither of the two bills made it in the sprint to an early deadline.

Still, the two bills were boosted by an arsenal of supporters—from lawyers and formerly incarcerated individuals to religious groups.

However, Baltimore County State's Attorney Scott Shellenberger mounted a fierce opposition to the bills. He emphasized the importance of punishment, pointing out that only the "most heinous of crimes" receive life sentences—premeditated murder and felony murder, first degree rape and first degree sex offenses, for example.

"When you are making the important, public-safety decision of should the worst of the worst be back on our streets," he said, "shouldn't the chief executive of the state have a say, especially when the parole commission works for the executive branch?"

INTO THE FREE WORLD

The season was just turning from spring to summer when Mitchell was released from prison in 2013. All told, he spent 37 years, six months, 19 days and 21 minutes behind bars—more than he had lived in the free world before his incarceration.

While Mitchell did his time, life ground on without him. Seven years into his incarceration, Mitchell's wife died of a heart attack, leaving their two young sons to be raised by their aunt. He said he wasn't allowed to attend her funeral—only to view her body, handcuffed and supervised by three guards, for half an hour.

But there were bright spots, too. In late May of 2010, Mitchell met a woman by the name of Regina in the prison visitation room. They started talking over the phone, and some 10 months later, they were married. As of March, they have been together for nine years.

And Mitchell is still in touch with the people he became close with during his time behind bars, though he feels bad knowing that many of them will likely never be released.

"I realize that whenever a crime's committed, there's always going to be victims," he said. "Some things you can never take back. . . [But] the majority of individuals, they just want to come out, want to have a family, enjoy their families and give back."

Even as prison populations are falling nationwide, the number of incarcerated people considered to be geriatric is quickly expanding --- riding on the wave of "tough on crime" sentencing practices that began proliferating in the 1980s. One report predicted that by 2030, people over 50 will make up one-third of the U.S. prison population.

Even as prison populations are falling nationwide, the number of incarcerated people considered to be geriatric is quickly expanding --- riding on the wave of "tough on crime" sentencing practices that began proliferating in the 1980s. One report predicted that by 2030, people over 50 will make up one-third of the U.S. prison population.