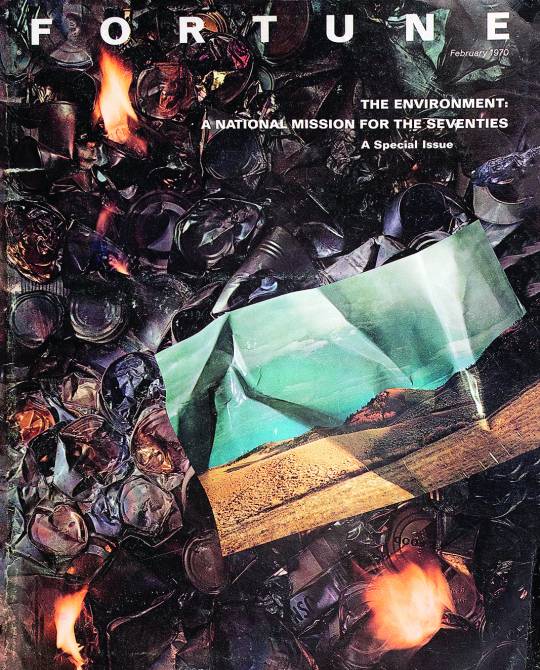

The February 1970 issue of Fortune magazine, published shortly before the first Earth Day. (Cover photographed by Dave Harp)

The February 1970 issue of Fortune magazine, published shortly before the first Earth Day. (Cover photographed by Dave Harp)"We know that our high-technology society is handling our environment in a way that will be lethal for us. What we don't know—and had better make haste to test—is whether a high-technology society can achieve a safe, durable and improving relationship with its environment."

That statement haunts me, for it is timely—but written 50 years ago, in an extraordinary issue of Fortune magazine, a leading journal of American capitalism. Fortune's February 1970 issue, just before the first Earth Day that April, recognized a "national movement bursting with energy, indignation and new members." Environmentalism.

We're 50 years out from Earth Day One now, and it's been 42 years since we began a study of Chesapeake Bay's systemic decline that led to today's way-unfinished business of restoring it.

I recommend finding that old Fortune. It's a chuckle to read the slick ads of the time: A full page, gorgeous sunset silhouetting a bathing beauty on a beach, with text, WE DIG JAMAICA. It's an ad for Anaconda Aluminum, bragging about expanding its Caribbean ore pits. And a sweet union-buster ad from Virginia's government—"Working is a privilege. Not a backache. I've worked in Virginia ever since Anne and I got married, and I've never been involved in anything like a strike." Also, the latest in fashion from "McCalls, the Magazine for Desirable Women."

But the issue's text, in article after article on the environment, is anything but dated, even after half a century:

The automobile is a "major menace" to the environment, from human health to suburban sprawl, to the quality of urban life. Public transit needs attention. Coal burning is going to make us sorry and unhealthy. Taxing pollution is worth considering. Sewage treatment plants had better start removing nitrogen and phosphorus that are sliming our waterways with algae. Agricultural runoff of the same nutrients is a well-recognized spoiler of Midwest waterways. Business leaders see a need for stronger federal leadership on pollution control. (The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency would soon be formed.) Pollution control was good for the economy if one looked beyond short-term profit.

The issue featured side-by-side pro-environment statements from President Nixon and Edmund Muskie, who would author the powerful Clean Water Act of 1972 and run against Nixon. Nixon had been advised not to let Muskie "outgreen" him.

Nixon would soon appoint a blue-ribbon Commission on Population Growth and the American Future, which would conclude that the U.S. population might stabilize around 226 million, and that would be a good thing. (It is at 326 million and climbing toward half a billion, and apparently that is now a good thing.)

Coincidentally, plant geneticist Norman Borlaug in 1970 was awarded the Nobel Prize for the Green Revolution, which did a lot to feed the world's hungry.

Those who tout his achievement as proof we can "invent" our way out of crises forget the caution of his Nobel acceptance speech: Higher-yielding crops had bought some breathing room, but unless agencies working on feeding us began to work with those trying to control population, we would not be sustainable.

So you look back and you think, how did environmentalism not better deliver on such a promising beginning? How did we blow Chesapeake cleanup deadlines in 2000 and 2010 and quite likely in 2025?

There was a lot of pushback by a lot of powerful and monied interests, from the fossil fuel industry to agriculture (the latter was mostly exempted from clean water laws). A politics that was bipartisan on environment has bitterly split now.

President Trump, with his seemingly pathological need to repeal environmental protections, is the deserving bogeyman of the moment. But I'd be writing this column even with "President Hillary Clinton" in the White House.

And there have been plenty of successes. Nationally, the air and water are cleaner. Around the Chesapeake, sewage pollution plummeted even as the population doubled. Crabs and rockfish are managed sustainably, and close to 10 million acres of the 41-million-acre Bay watershed is protected.

Where we have succeeded, common ingredients include leadership, good science that translated into accountability, enforcement and adequate funding. Where these lagged—well, think oysters, shad, agriculture, Pennsylvania.

Some days, I'm tempted to say we have about the environment we deserve, the Bay we deserve, though that sounds harsh.

But we vastly favor cure over prevention, treating symptoms rather than dealing with root causes. Fortune in 1970 said pay more attention to the environmental impacts of new technologies and products before bringing them to market. Say it again, Sam.

Similarly, it is considered enough to focus on the impacts of people already on the planet while ignoring and even encouraging population growth.

Or is our problem rooted in capitalism itself? Looking back at the 1970s, the enthusiasm, the wide buy-in, the good economy, the passage of strong laws, you can understand why environmentalists believed they could get where they wanted by working within the system. Certainly, the editors of Fortune believed that devoutly.

I think capitalism as now practiced in the United States, with its powerful "endless growth" bias and our outgunned environmental regulators, will not likely produce a healthy Chesapeake. I also think environmentalists are in denial about how radical a shift is needed to co-exist durably, safely, "improvingly" with the rest of nature—and to embrace limits.

So we go on, endeavoring earnestly to return a Bay with 18 million citizens back to something like the water quality and abundance it enjoyed with 8 million people—even as we push toward 24 million.

In an essay some 40 years ago, called Saving the Bay, I wrote this: "Will we save the Bay? I know we will always be trying, but 'saving the bay' can become almost a state of grace, like tithing, allowing us to proceed comfortably with business as usual in the rest of our lives."

I guess you could do worse. I still hope we can do better.

Tom Horton has written about Chesapeake Bay for more than 40 years, including eight books. He lives in Salisbury, where he is also a professor of Environmental Studies at Salisbury University.