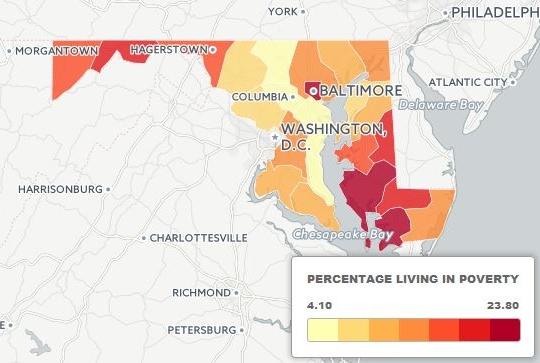

The percentage of people living in poverty is highest on the Eastern Shore and in Western Maryland, and lower in more affluent counties closer to Washington and Baltimore. The one exception: Baltimore City, where approximately one-quarter of the population lives in poverty. (By Ben Harris)

The percentage of people living in poverty is highest on the Eastern Shore and in Western Maryland, and lower in more affluent counties closer to Washington and Baltimore. The one exception: Baltimore City, where approximately one-quarter of the population lives in poverty. (By Ben Harris)POTOMAC, Md. (Nov. 3, 2016)—Upon arriving in Stevensville after crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, drivers will notice something peculiar. It will take some time to set in, but as they continue east it will dawn on them.

There are Donald Trump signs everywhere.

There are so many Trump signs one might be tempted to question the validity of election forecasts assigning the New York real estate mogul a less than 1 percent chance of winning Maryland.

The Eastern Shore is far and away the reddest territory in the Old Line State. The region boasts Maryland's lone Republican representative in Congress, Rep. Andrew Harris of Cockeysville. Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney bested President Barack Obama in the district by almost 23 points in 2012, while Obama carried the rest of the state by 25.

There is a clear gap in ideology between the state's blue urban center and its red outskirts. A major reason is economics, said Stella Rouse, the director of the University of Maryland's Center for American Politics and Citizenship.

Maryland is, by several measures, the nation's wealthiest state. The U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey places the state's median household income at $75,847, up roughly 10 percent from 2010.

But much of that growth and prosperity is concentrated between the metro areas of Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

Wages in the eastern and western rural regions of the state haven't kept pace with its urban core, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

These blue-collar areas mimic the economies of Rust Belt states like Ohio and Indiana, where wages aren't as high and the loss of manufacturing jobs has offered Trump more of a receptive audience. Trump leads Clinton by 7 points in Indiana and 2.5 points in Ohio, according to press time polling averages from RealClearPolitics.

"Trump speaks to American workers," said Tim Craig, a small business owner from Carroll County and the chair of Carroll County for Trump. "We have a jobless recovery, where we actually have more kids graduating college or high school entering the workforce and we aren't creating jobs."

For Craig and other Trump supporters in Carroll County, economics is the driving force behind their votes. Trump's stance on manufacturing, trade and even immigration resonates well with Craig and others who feel the same about the state of the economy.

But that rhetoric is having a tougher time connecting with voters in Maryland's traditionally Democratic urban centers.

On its surface, the region's blue tilt is confusing. One would expect its wealthy voters to embrace Republican support for tax cuts and increased defense spending—the latter driving much of the Washington-area economy.

But in Maryland, prosperity seems to free voters to focus on social policy, according to Rouse.

"A lot of liberals are much less stuck on the fact that an economic policy has to advance their own personal interests," she said. "People might love to have tax cuts, but they also prioritize (social) issues, and therefore are willing to sort of give up perhaps personal tax cuts or personal financial benefits."

Bernie McMahon, a Democrat from Rockville living comfortably retired after 30-plus years of work for the federal government, fits that mold.

"I worry about the economy, but I also worry about minorities and the problems minorities are facing," he said. "I was so turned off by Donald Trump that that became the driving factor of my vote. I really feel that man would be a danger to the country."

The structure of Maryland's urban economy, a more white-collar area than its rural counterparts, also makes it rough territory for Trump.

Polls show the state's college-educated voters overwhelmingly back Clinton, and in Howard County and Montgomery County, over 60 percent of the adult population has an education beyond a high school diploma, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Economics alone cannot explain the ideological divide between rural and urban voters. Demographics play a large role as well.

White Marylanders make up 50 percent of the state's total population, according to the Henry J. Kaiser Foundation. Only Texas, California, New Mexico, the District of Columbia, and Hawaii report lower figures.

But like wealth distribution, much of the state's minority population is concentrated in Maryland's urban communities. Here, wealthy voters, who prioritize social policies and non-white voters, who tend to be more open to government intervention according to Rouse, combine to create a uniquely liberal coalition.

For many of these voters, like Rockville resident Sarah Ahmed, Trump's treatment of immigrants, minorities and women has been disturbing and is at the top of their list when heading to the polls.

"I chose to vote to sort of stop that kind of mentality from spreading," Ahmed said.