COLUMBIA, Md. (June 2, 2016)—One of three national bond rating agencies, S&P Global Ratings, cited important differences with State Treasurer Nancy Kopp about how Purple Line debt is recognized in its

May 26 opinion supporting Maryland's $1 billion bond sale next Wednesday. S&P says it's going to county Purple Line payments as debt; Kopp says it doesn't have to be.

That opinion by the Standard & Poor's sovereign bond division and those of Fitch and Moody's rating firms were otherwise complimentary of Maryland's financial picture and fiscal controls ahead of Maryland's only bond sale set for this year.

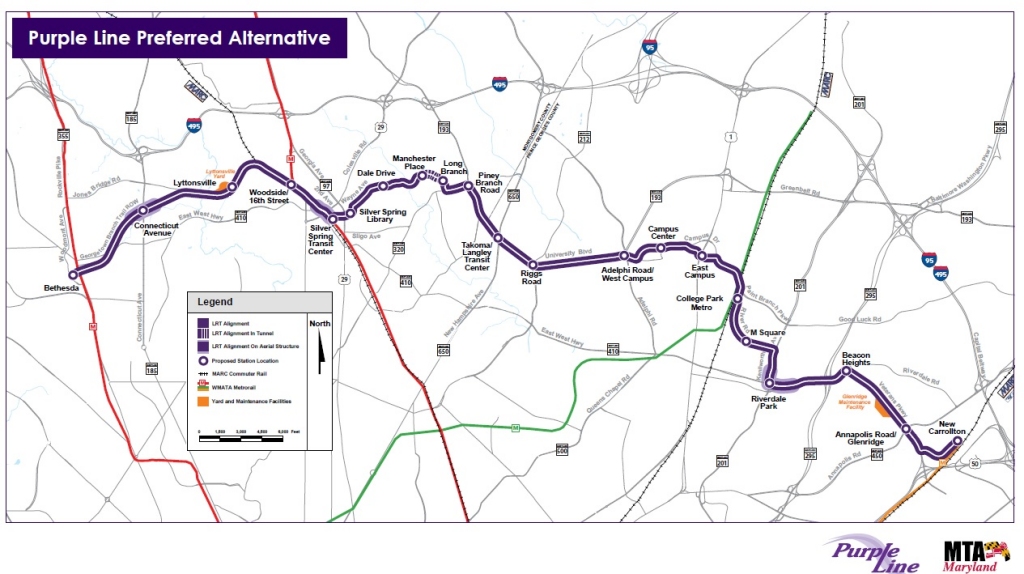

The light-rail Purple Line will be built under a $5.6 billion public-private partnership (or P3) by Purple Line Transit Partners, and is expected to begin service in 2022. The ambitious arrangement was conceived as a way to transfer specific risks that can be more efficiently managed by the private sector, to design, build, operate and borrow money to help pay for the 22-station transportation project, crossing Montgomery and Prince George's counties from the Bethesda Metro station to the New Carrollton Metro.

The project's scope and duration represent a first in Maryland and the P3 arrangements have drawn national interest in the project's success.

To get this far, the project has withstood at least four years of work by state planners, and millions of private-sector investments (not to mention the concurrence of successive administrations.)

It now has progressed from a mountain of paper and engineering drawings to talk of mobilizing contractors to break ground—after the state inks a deal for $900 million of fresh grant monies from Uncle Sam late this summer.

Complex deal

The 900-page contract simply covers administration of the deal—its terms are supplemented by thousands of design plans, drawings and construction specifications—likely making it the most complex contract in the state's history.

It's so complex that the parties and stakeholders likely won't know how the provisions operate in practice until several years' experience working out equitable interpretations of key contract provisions. In a sense, the parties needed to sign the contract to find out what's in it.

P3's terms intended to raise capital outside debt constraints

Maryland's Department of Transportation (MDOT) tried to structure capital financing in a way so Maryland's payments to extinguish debt originated by the P3 contractor would not be counted as tax-supported state debt. It set up a paper firewall:

P3 debt carries no pledge of state assets and no recourse or repayment guarantee by Maryland; and

MDOT will set up a trust agreement managed by a trustee designed to match the State's payments to the P3 used for debt service with fare revenues (from MARC and the Purple Line.) Such matching would objectively show that debt incurred by Purple Line Transit Partners was paid exclusively with fares or other non-tax derived State revenue.

MDOT did so for good reason. Tax-supported debt is subject to limits controlled by debt watchdogs in the legislature and the Capital Debt Affordability Committee responsible for fiscal control and helping protect the state's credit rating. Maryland policy is to keep tax-supported debt at 4% or less of Maryland personal income, and tax-supported debt service at less than 8% of state revenues.

If the purple line could be paid for outside these debt limits, then Maryland could assign maximum borrowing capacity to pay for other necessary capital projects, such as roads, bridges, schools, and hospitals. Conversely, if Purple Line debt must be counted as part of the debt cap, then other capital projects might need to be deferred or cancelled.

Importantly, however, S&P doesn't decide whether Maryland includes Purple Line borrowings in its debt constraints. As a sovereign entity, the state makes that determination.

Debt analysis needed to be finished quickly

State Treasurer Kopp had 30 days by law to evaluate the substance of the P3 contract and MDOT's debt firewall scheme and write an opinion letter needed for the Board of Public Works' approval. BPW needed the opinion to assure itself about whether Purple Line borrowings are tax-supported debt.

Kopp consulted with the state's outside auditor, Comptroller Peter Franchot, and the Office of Attorney Genera. In

her April 3 letter, she informed BPW on which she serves that the Purple Line will be paid for without tax-financed debt.

In a recent legislative hearing, however, she diplomatically told a state Senate committee that lawmakers might want to change the law to allow for a longer contract-review period. "Thirty days," Kopp told the panel, "may not really give everybody enough time."

Kopp's official opinion on the debt was reasonable, but not as conservative as it could have been, but S&P didn't buy it.

S&P didn't buy it

According to its bond rating report, S&P "will incorporate the net present value of the milestone payments in the state's net tax-supported debt ratios through the period before Maryland starts making availability payments for the P3 project. Once P3 project construction is complete and operational, we will incorporate availability payments that are not supported by project revenue into our estimates of the state's net tax-supported debt ratios."

In other words S&P will rate future Maryland bond issuances using higher tax-supported debt levels than the state does. The difference could be as high as $3.1 billion, according to figures

published in the Washington Post.

What's all this mean?

The differences, if any, between S&P's and the state's tax-supported debt numbers right now are unknowable, so they may or may not be significant. If they are, the state may want to align its calculations with S&P's more conservative methodology, although that could reduce the amount of tax-supported bond resources available for other projects.

"This is a project that's a big deal, and it's going to be a big deal for a long time," former Maryland Transportation Secretary James T. Smith Jr. told Board of Public Works in 2013. "If this works .?.?. we want to make this a model" for some other large infrastructure projects, he added.

There will be a lot of lessons learned by all parties and the state may need a decade before they know how this works.

Bond-rating Firm Differs with Treasurer Kopp Over Purple Line Debt

The light-rail Purple Line will be built under a $5.6 billion public-private partnership (or P3) by Purple Line Transit Partners, and is expected to begin service in 2022.