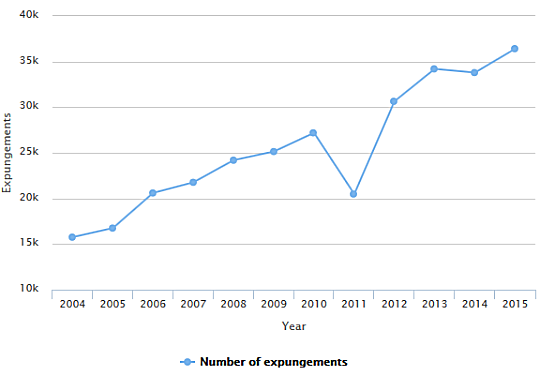

The number of expungements has more than doubled over the last 12 years, because of new laws that expanded eligibility. The figures shown here do not include expungements of people who were held and released without being charged. (It's unclear why the number of expungements dropped between 2010 and 2011). (Chart: Marissa Laliberte and Jason Dobkin)

The number of expungements has more than doubled over the last 12 years, because of new laws that expanded eligibility. The figures shown here do not include expungements of people who were held and released without being charged. (It's unclear why the number of expungements dropped between 2010 and 2011). (Chart: Marissa Laliberte and Jason Dobkin)ANNAPOLIS—Stephanie Good, 28, of Baltimore, said she served time in prison because she could not find and keep a job.

Now, Good says she can't find a job because she served time in prison.

In 2015, Good was released from the Baltimore County Detention Center after serving eight months for a violation—failure to maintain a full-time job—of probation for a felony theft from five and a half years ago, she said.

Good said employers recently rescinded two job offers because of her criminal background.

"A lot of people make one mistake and it causes a downward spiral," Good said.

Tuesday, Good and other advocates rallied in support of bills they say would remove barriers to employment for ex-offenders by expanding expungement policies.

The General Assembly last year passed legislation that allowed for the shielding of certain nonviolent misdemeanor convictions from public view, as well as the expungement of "non-convictions,"—cases that are acquitted, dismissed or dropped—and convictions for acts that are no longer a crime, according to Caryn York, senior policy advocate with Maryland's Job Opportunities Task Force.

After expungement legislation took effect on Oct. 1, 2015, the number of petitions for expungement filed in District Court through December 2015 increased by 50.55 percent compared to the number of petitions filed during the same period of 2014, according to a legislative analysis.

But some lawmakers say more should be done to help offenders re-enter society.

"We have to be honest with ourselves that only allowing the shielding or expungement of misdemeanor crimes is simply not enough," said Delegate Jill Carter, D-Baltimore.

Supporters at the rally said the legislation could help reduce recidivism, bolster the state's economy and reform a system of mass incarceration that disproportionately affects poor people and minorities.

One proposal would allow for the partial expungement of acquitted or dropped charges when they are attached to related convictions. If an individual is charged with a number of offenses relating to the same incident, and found guilty of only one or some of them, he or she cannot expunge those other charges, leaving some people with "very scary looking" criminal records, York said.

"When employers see this record they're not necessarily looking at guilty versus not guilty, they're seeing that whole list of charges and they're judging individuals on that," York said. "And that's just not fair."

A different bill would make the expungement of non-convictions automatic, and another, Carter explained, would allow individuals to petition for hearings for expungement of nonviolent felony convictions.

In a House Judiciary Committee hearing, Delegate Curt Anderson, D-Baltimore, testified that expungement legislation would give individuals in the city and around the state the opportunity to "get on with your life."

"What we're looking to do is to give that second chance to every single person who's had a problem at an earlier age," Anderson said. "Having a criminal record—almost anything on your criminal record—is an obstacle to getting a job. It's an obstacle to getting a loan for school or even getting into college. It's an obstacle to housing. There are so many barriers artificially it throws up."

But some of these proposals may be difficult to implement, said John Morrissey, chief judge of the District Court of Maryland. Morrissey testified that the expungement process is labor-intensive and consists of multiple steps, including the physical destruction of entire files. Partial expungement, of just some of the charges in one case, would require "extensive decision-making" that could not be delegated to a clerk, he said.

Morrissey said partial expungement would result in "an extraordinary increase in the number of petitions for expungement," and would create the need for at least 16 new staff members for handling petitions.

The bill's supporters have introduced an amendment that would apply partial expungement only to electronic records, York said.

The state's judicial branch also opposed a bill relating to expungement of "invalidated" arrests because its language is somewhat unclear and overly broad, Morrissey said. He also said Carter's bill authorizing a person convicted of a nonviolent crime to file a petition for expungement is unnecessary because current law allows the court to grant a petition at any time, on good cause.

U.S. Rep. Donna Edwards, who is running for a U.S. Senate seat, said at the rally that she supports the legislation because she believes in "second chances."

"I'm here for all those young men and women who just want to be productive, go to a job, meet their responsibilities without the stigma because they messed up. And that's all that any of us want," Edwards said. "Anybody that wants an education and a job should not be held back because they made a mistake."