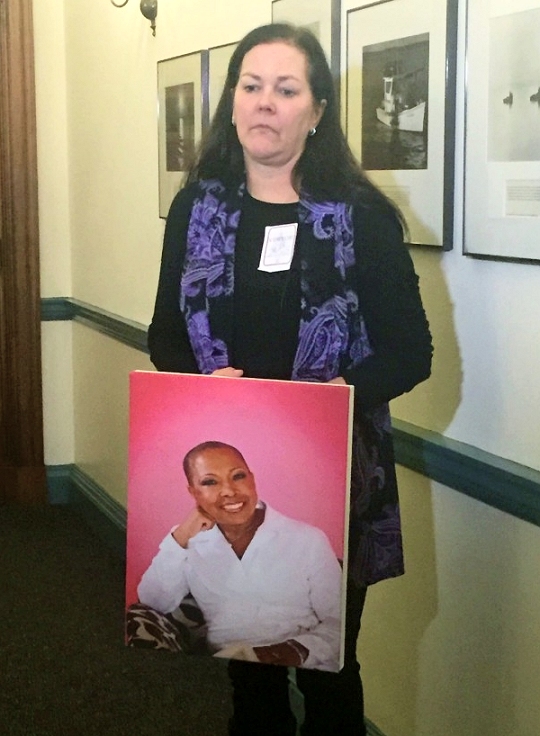

Kelley Lange with a portrait of Marlene King. (Photo: MarylandReporter.com)

Kelley Lange with a portrait of Marlene King. (Photo: MarylandReporter.com)ANNAPOLIS (Feb. 22, 2016)—In an emotionally charged, eight-hour hearing Friday, more than 30 advocates made heartfelt pleas to lawmakers in an effort to make Maryland the sixth state to allow terminally ill patients to take their own lives with the assistance of lethal drugs.

Last year was the first time state lawmakers introduced "death with dignity" legislation. However, the bill did not make it out of committee.

Back for round two, bill sponsor Del. Shane Pendergrass, D-Howard, has urged her colleagues to reconsider and pass HB 404. She, as well as other proponents, believe that a terminally ill individual has the right to determine his or her own fate.

"Having the medication means knowing you can skip the very worst, the very last part of dying if you choose," said Kim Callinan, the chief program officer at Compassion and Choices, a nonprofit organization dedicated to expanding and raising awareness for end-of-life care.

But religious groups, medical doctors, several disability rights advocacy groups and other opponents raised concerns about the implications of condoning physician-assisted suicide, how it would work in practice and whether someone could miraculously survive if given the chance.

"What we are asking for is merely an option," Callinan added. "It is the option for a terminally ill adult with no hope of a cure to voluntarily request a prescription for medication from their doctor that they can self-administer so they can die peacefully in their sleep. This option is known as medical aid in dying."

However, if this bill becomes a law, medical aid in dying would only be an option for those who would qualify.

Many steps to qualify

In order to qualify, an adult with a terminal illness must file a request on three separate occasions, once in writing and twice verbally. During this process, the individual seeking physician-assisted suicide must consult two different doctors.

By the end of this multi-step process, the individual's attending physician must confirm that the patient possesses the mental capacity to make medical decisions, is a Maryland resident, has six months or less to live as well as the physical ability to self-administer the life-ending medications.

"Living with metastatic cancer is not easy. Dying from it is harder," said Kelly Lange, who has terminal breast cancer. "When my time comes, I want to die on my own terms, so that I can decide when I have had enough pain. I can decide when I am ready. Please, give me this choice that those of us with cancer so desperately need."

With no-end-of-life option currently available, cancer patients like Lange are acutely aware of the excruciating pain they might experience when dying.

Callinan has spoken to supporters of the bill across the state. The stories she heard were often about cancer patients.

"Their doctor has shared what might be in store for them, excruciating pain in the bones or at the tumor site that can not be relieved even with massive doses of morphine," Callinan recalled. "For those with cancer in the lungs, you can have such difficulty breathing that eventually you drown in your own fluids."

And even if one was not personally diagnosed with cancer, a loved one suffers too.

That feeling was all too familiar for Eric King, a Baltimore resident. King was the primary caregiver for his wife, Marlene, who lost her seven-year battle with breast cancer late last year.

Marlene testified in support of this bill last legislative session. Now, King is continuing her fight because he does not want anybody else to suffer as he and his wife did.

"For seven years I slept with cancer, I was awakened by cancer, I've smelled it, felt it, watched it grow, disfigure and gradually deteriorate the life of a fine, fiery, fantastic mother and wife," King said.

Cancer second leading cause of death in Maryland

According to a 2014 report by the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, more than 10,000 Marylanders died from cancer—the second leading cause of death in the state.

With such a high death rate, Lange called medical aid in dying "critical."

"Marlene is a perfect example of why we need this legislation now—we can't afford to wait," said Lange.

Opponents call it suicide

While proponents of this bill believe that medical aid in dying is both a personal right and a much-needed humane option to an otherwise painful death, opponents consider it suicide.

"Physician-assisted suicide is not a 'natural cause' of death, and it is dishonest to consider naming it anything otherwise," Christine Sybert, a pharmacist from Pasadena, said. "We have an innate desire to survive, to fight, to live."

"While it is natural to die, it is unnatural to want to die," Sybert added. "Anyone who wants to die, and seeks sanctioning from the state to permit them to do so, is suffering from a mental disorder of depression or hopelessness."

Callinan rejected the notion of medical aid in dying being synonymous with suicide.

"Suicide involves people who are so severely depressed that they no longer want to live," she said. "Medical aid in dying involves individuals who would love to live, but they can't. A disease is taking their life—and soon."

Opponents were not buying it.

"I find it interesting that we, as a nation, spend millions of dollars on anti-suicide campaigns a year," said Chelsea Gill, a senior studying political science at UMBC. "Suicide is looked down upon in this society, as it has been for many decades. And now we want to make suicide acceptable? What kind of message does that send to Americans?"

Vulnerable patients

Many of opponents fear that this legislation could put other vulnerable groups—like those who suffer from depression—at risk, as well as make way for potential abuse.

"The question is, where do we draw the line between a life worth living and not worth living?" said Kim Klump, the president of a suicide awareness and prevention nonprofit organization.

"There are too many factors which may increase the tendency of many, especially the disabled, poor and less empowered, to abuse physician-assisted suicide or be victimized by it, and use it in a way which promotes the suicide of those who may seek this as a viable alternative to a life which they find burdensome or undignified," Klump added.

"This legislation would lead to many unintended consequences for individuals with disabilities who are often targets of coercion and abuse," said Samantha Crane, director of public policy for the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. "Although few people are expected to use the law, it would endanger many more lives for people with disabilities who already feel like a burden to family and loved ones."

"People with intellectual and developmental disabilities have historically faced discrimination and lack of access to medical care based on their perceived value," said Cristine Marchand, executive director of The Arc Maryland. "Assisted suicide raises significant concerns for people with disabilities as well as those who will acquire a disability as a result of a terminal diagnosis who are perceived as less valuable."

Dr. William L. Toffler, the national director for Physicians for Compassionate Care, referred to his experiences working in Oregon—a state that has a physician-assisted suicide option for nearly 20 years.

"Many individuals who have been labeled 'terminal' and given overdoses by their doctors were actually found to be depressed, yet the doctor who gave them the overdose had not recognized the depression."

Toffler, who has practiced medicine for 35 years in Oregon, also mentioned that since physician-assisted suicide became an option in 1997, he had encountered more than 20 patients who had inquired. Most of his patients, though, did not have a terminal diagnosis.

Advocates believe that the bill has the necessary safeguards to ensure that the patient is protected.

In addition, Callinan and other end-of-life advocates repeatedly emphasized that this would be a voluntary choice for both the patient and health care providers.

"This is a sensible bill," said Dr. Susan Panny, a retired physician who worked in public health at the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. "The bill has provisions to ensure that no patient is coerced, that no physician is coerced into prescribing drugs against their conscience and that no health care facility is coerced into providing this option against their policy."

Alessia Grunberger can be reached at agrun0502@gmail.com