ANNAPOLIS (Feb. 5, 2016)—Maryland must use its status as a hub of technological resources to ensure its own cybersecurity, Vice President and Chief Internet Evangelist for Google Vinton Cerf told state legislators and industry experts Thursday.

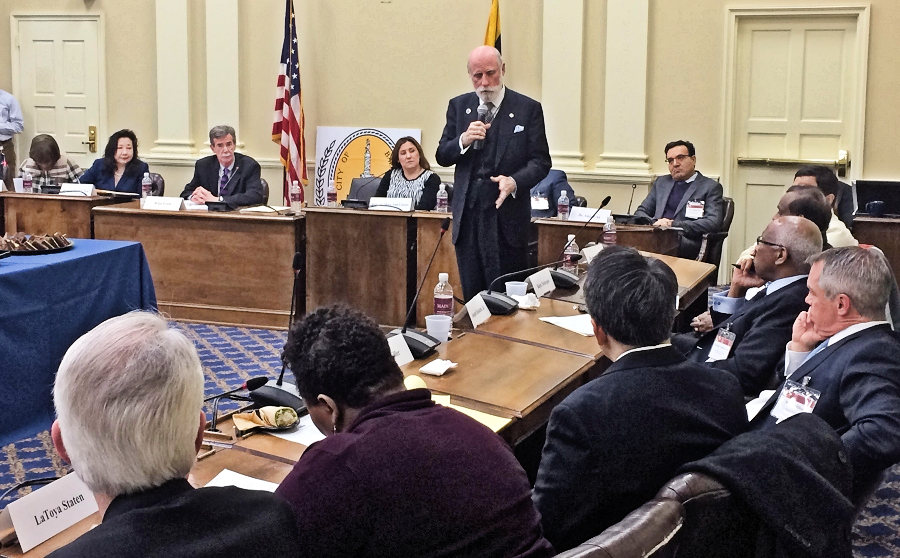

Speaking at this year’s first meeting of the Maryland Cybersecurity Council, an advisory panel of government officials and private-sector security professionals, Cerf said the commission’s local collection of experts can help address data vulnerabilities on every level, from corporate to public.

“Maryland has made an enormous amount of progress and shown leadership in the cybersecurity space, so you have a lot to be proud of,” Cerf said.

Even the simplest data can expose your privacy, Cerf said, and in a time when every person who owns a smartphone is carrying around hundreds of millions of lines of code in their pocket, security is more important than ever.

“I can’t think of anything more critical to our future than figuring out how to secure ourselves in cyberspace,” Cerf said.

One reason that data is vulnerable is because software always has bugs and programmers have not yet figured out a way to write perfect code, Cerf said. Additionally, he said, education is key to helping individuals secure their own data.

Home to federal agencies like the National Security Agency and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, as well as university cybersecurity programs, Maryland needs to take advantage of its resources and get ahead of the next large-scale breach, said state Sen. Susan Lee, D-Montgomery.

“We shouldn’t be responding. We need to be proactive,” said Lee, who was the primary sponsor for the bill that established the council last year.

The council’s goal is to make recommendations about how best to ensure that Maryland residents, business and governments are “as free from cyberattacks as we can make them,” said Attorney General Brian Frosh, the council’s chair.

“You’ve got folks out there who want to do everything they possibly can to steal technology, to disrupt services, and to steal money,” Frosh said.

The council’s membership list includes state legislators, representatives from state and federal agencies, attorneys and private security analysts, university program directors, and members of the military and police.

Lessons about cyber-technology should begin as early as elementary school so that every person understands the importance of data security, he said.

Shortages in the technology workforce have become a “tremendous” issue for private-sector firms, but universities have been stepping up their cyber-education programs to fill those vacancies, said John Abeles, president and CEO of cybersecurity consulting group System 1 Inc.

“I can’t find enough qualified people to do the work I’m doing,” Abeles said.

Sometimes called “The Father of the Internet,” Cerf has had a prestigious career in the cyber world. Before becoming vice president of Google, Cerf worked at the United States Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency where he helped develop the early stages of what would eventually become the Internet and was awarded the U.S. National Medal of Technology in December 1997.

Lee, co-chair of the council’s policy and legislation subcommittee, has previously sponsored cyber-security laws that prosecute hackers who attack state infrastructure.

Maryland sees thousands of cyber attacks every day that range in size and design, said Maryland Secretary of Information Technology David Garcia, who serves as chair of the council’s incident response subcommittee. Though these attempts are common, they are typically smaller scale, such as phishing attacks or denial-of-service attacks, he said.

“We see those every single day. How often do they get through? Sometimes,” Garcia said. “Sometimes, we may have to change an IP on a machine, we may have to redirect service.”

In 2014, the University of Maryland was hit with a massive data breach in which the personal information of more than 309,000 students, alumni and staff was compromised. According to an email sent by campus President Wallace Loh, the information included names, Social Security numbers and dates of birth.

The University of Maryland breach was a “very unique” level of compromise, Garcia said.

Most people will get hacked at some point, he said, and his subcommittee will address at what point government officials or agencies like the attorney general or the FBI will need to get involved.

“There’s a saying in the community. There’s two types of people: Those who know they’ve been hacked and those who don’t know they’ve been hit,” he said.

Cybersecurity Council is 'Critical' to the State, Says Google VP Vinton Cerf

Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh, left of the American flag, and state Sen. Susan Lee, D-Montgomery, left of Frosh, listen to Vinton Cerf, vice president of Google and keynote speaker at this year's first meeting of the Maryland Cybersecurity Council on Thursday, February 4, 2016. (Photo: Leo Traub)