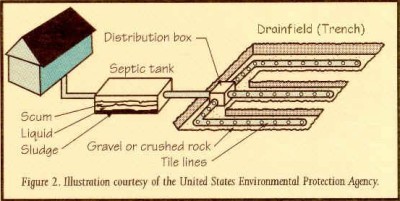

A schematic of a drainfield-based septic system, commonly used in southern Maryland.

Imagine if one of our major automakers proposed a model line of gas-wasting, air-fouling vehicles that used 60-year-old technology. Unthinkable of course; but it's little different than what homebuilders and developers propose when they plan most new rural subdivisions.

Their outdated model lineup combines sprawl development — a hugely wasteful use of land — with septic tanks, the highest polluting form of waste treatment largely unimproved for more than half a century.

Proposals to change this — most lately Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley’s attempt to ban most development on septic tanks — are met with predictable cries from builders and land speculators. Housing will become unaffordable, the economy will crash, development will scream to a halt, they say. Their cries remind us of the auto industry-s doom-saying as it fought seat belts, airbags, higher mileage standards and pollution controls.

We’re unused to thinking of development as a technology, but it is. Sprawl, the building on large lots outside areas planned for more compact growth, is bound to septic tanks. You don’t have one without the other. Septic tanks won’t work on small lots because they need space to filter sewage. Public sewer doesn’t serve spread out development because it's too expensive to run lines.

A septic tank, a concrete tank buried somewhere in the yard, into which your toilets flush, is probably what you have if you aren’t hooked up to public sewage. Created to replace outhouses and cesspools, septic tanks remove bacteria from wastewater by settling out solids and percolating the water through underground drainage fields.

Unlike a modern sewage treatment plant, septic tanks were never designed to remove nitrogen, the Bay’s biggest pollutant. Indeed, they facilitate the water soluble nutrient’s passage into groundwater and thence into streams, rivers and the Chesapeake.

How much nitrogen a septic tank emits compared with a sewage treatment plant depends on its location; but it can be from four to 10 times as much according to water quality regulators. A newer, more expensive type of septic tank can cut nitrogen in half, but still cannot match what a treatment plant can remove. Only Maryland requires these new tanks, and then only within a thousand feet of tidal waters.

Septic tanks are the source of about 6 percent of the nitrogen that pollutes the estuary. This may not sound like a lot until you look at the huge pollution reductions every state in the Bay watershed must make.

But Governor O’Malley’s plan goes beyond controlling nitrogen.

The governor recognized that nearly a third of the quarter million or so new households projected for Maryland by 2020 is likely to be on septic tanks. His proposal — no development of five or more homes that isn’t hooked to a sewage treatment plant — would push this growth toward planned areas. It would do more to rein in sprawl than decades of talking about “Smart Growth.”

The adverse impacts of sprawl go far beyond water quality. They include loss of farms, forests and wetlands; more air pollution from longer commutes; and higher taxes from added costs of school buses, utilities, fire, police and roads.

None of this has overcome development interests, which are sometimes augmented by farmers wishing to maximize their options to cash out. Perhaps O’Malley’s drawing a clear link between bad land use and bad waste management can succeed where reciting sprawl’s litany of problems has failed. Farmers and other landowners, who want to carve out a few lots for their children or for income, would still be allowed a few under the governor’s proposal.

There would be adjustments and short-term pain for developers, whose industry makes up about a fifth of Maryland’s economy; but think of the adjustments sprawl development and water pollution force on the fifth of Maryland’s economy that comes from farming and fishing.

Pennsylvania and Virginia have more rural poor than Maryland, whose poor are largely urban, so septic restrictions might be somewhat different there.

What the three major Bay states share, is a substantial shortfall in the plans they have submitted to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to reduce pollution from septic tanks.

One irony that should not derail the Maryland proposal, but must be dealt with, is that septic tanks do not let the polluting phosphorus in human waste enter the Bay, because it binds to soil in the ground. To the extent that development switches to sewer from septic, sewage treatment plants will have to remove more phosphorus, or reducing one Bay pollutant could increase another.

Maryland’s legislature will study the governor’s proposal this summer. We hope it comes back strong, because it provides a rare opportunity to improve two of the Bay’s most glaring problems at once, excessive nitrogen and sprawl development.

Tom Horton covered the bay for 33 years for The Sun in Baltimore, and is author of six books about the Chesapeake. He is currently a freelance writer. Distributed by Bay Journal News Service.