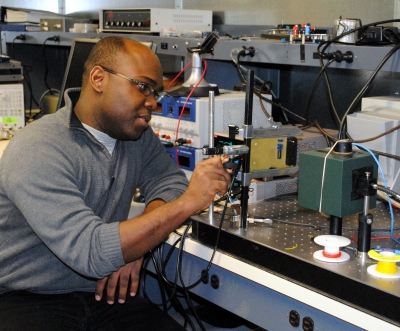

Mark Dandin, 28, a doctoral student who moved to Maryland from Haiti more than a decade ago, performs research in the Integrated Biomorphic Information Systems Lab at the University of Maryland, College Park. (Capital News Service photo by Steve Kilar)

WASHINGTON (January 28, 2011) — Mark Dandin's face lights up when he talks about detecting biological food contaminants. Anshu Sarje grins from ear to ear when she describes designing more efficient electrical circuits.

Dandin and Sarje — doctoral student researchers in the Integrated Biomorphic Information Systems Lab at the University of Maryland, College Park — do not have much in common beyond their shared workspace and enthusiasm for engineering.

Dandin, 28, was born in Port-Au-Prince, the Haitian capital, and moved to Maryland more than a decade ago. Sarje, 30, received her bachelor's degree in India, where she grew up, and moved to Maryland eight years ago to pursue advanced education.

He has a green card and is a permanent resident of the United States. She is on a student visa, which allows her to stay in the U.S. as long as she is studying.

They do share one trait, however, when compared with their peers born in the U.S.: As members of Maryland's foreign-born population, they face a significant income gap.

On average, Maryland's foreign-born workers earn 91 cents for every dollar earned by a native worker of the same age, with the same education and in the same type of job.

The gap is even more extreme among highly educated workers.

Foreign-born engineers with doctoral degrees — a group that will describe Dandin and Sarje when they graduate — earn only 70 cents on average for every dollar their native counterparts pocket in Maryland. Highly skilled workers bear the heaviest burden of the income gap.

In fact, low-skilled, foreign-born workers in Maryland often make more than natives. Foreign-born construction laborers, for instance, make $1.48 on average for every dollar earned by their native peers.

In the State of the Union address Tuesday, President Obama called on Congress to reform America's immigration laws and "stop expelling talented, responsible young people who could be staffing our research labs or starting a new business, who could be further enriching this nation."

In 2008, Gov. Martin O'Malley — a longtime supporter of assimilating highly educated immigrants into Maryland's science and technology sectors — created the Maryland Council for New Americans. The council was charged with developing policies to aid immigrant integration and maximize foreign-born workers' earning potential.

"Twenty-six percent of high-skilled recent immigrants work in unskilled jobs, and 40 percent of immigrant adults are Limited English Proficient ... resulting in lower wages and un-utilized skills," the council said in a 2009 report.

The report, titled "A Fresh Start: Renewing Immigrant Integration for a Stronger Maryland," concluded: "Unlocking the tremendous potential of these workers should be among Maryland's highest priorities."

"There's definitely disparity," said Margaret Kim, a member of the council, who has seen firsthand that Maryland immigrants face the realities that create income differences. Kim and her husband, Dr. Victor Kim, have hosted foreign-born doctors who tried to get work in Maryland.

Language barriers, residency requirements and professional examinations all make "bridging that gap" — translating a professional position abroad into an equal-paying job in Maryland — difficult, said Kim.

One foreign-born doctor the Kims hosted, a cardiology professor from South Korea, easily passed domestic exams but could not find a hospital that would hire him because he was not fluent in English.

His experience is not uncommon. College-educated immigrants who study in the U.S. earn a higher average income than those who receive their degrees aboard — regardless of how long a foreign-educated immigrant resides in the U.S. — according to a report published by the Migration Policy Institute in 2008.

Another factor contributing to income disparity, Kim said, is the discriminatory "glass ceiling" immigrants may face.

Kim, a U.S. native of Korean descent, runs medical clinics in Howard County geared toward uninsured and low-income Latino immigrants. But before opening the clinics with her husband in 2005, she worked as a telecom executive.

This experience, Kim said, showed her that wage discrimination based on gender, race and national origin exists.

Hurdles to economic equality encourage many immigrants to "become small business owners and create their own opportunities," Kim said.

The major factors that influence the foreign-born population's earning potential include linguistic disadvantage, the length of time an immigrant has been in the U.S., cultural respect for education and the strength of the immigrant's social and professional networks, said Gary Burtless, a labor economist with the Brookings Institution.

"The wage deficit shrinks the longer that the foreign-born person has been in the U.S.," Burtless said.

Immigrants often choose to give up social status and come to the U.S., Burtless said, because their earning potential — even in jobs below their skill level — is better here than in their native country.

"We pay our carpenters better than they pay their colonels," Burtless said.

With regard to legal immigration, Burtless does not think that discrimination plays a significant role in creating the foreign/native pay gap.

"It's an ill-advised leap to think that discrimination is the cause or that (immigrants) are, on the whole, unhappy," Burtless said.

But even for Dandin and Sarje, who have been in the U.S. for many years and are familiar with the American job-seeking culture, immigration policies loom as they approach graduation.

Dandin wants to continue his research in an academic setting or be part of a technology startup. But if he is unable to get a university job — increasingly scarce at government-funded research institutions — he knows his industrial job options are limited.

For instance, Dandin cannot work for firms that require a security clearance because he is not a citizen.

"It's just something I haven't done yet," Dandin said of applying for U.S. citizenship, although he does not anticipate leaving Maryland unless he receives a university job elsewhere.

"It is home now," Dandin said.

Sarje's career path has already been influenced by U.S. immigration policy. Upon graduating with a master's in biomedical engineering, she had difficulty finding a job in the mid-Atlantic region that did not require a security clearance.

Her academic adviser recommended she pursue a doctoral degree in electrical engineering — her interest since college — in part because jobs open to non-citizens would be easier to find.

Sarje would like to stay in Maryland after graduation. U.S. companies, she said, are on "the cutting edge" of circuit design.

"I love Maryland," Sarje said.

The data used in this Capital News Service analysis is from a 2006 through 2008 sample of the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey. Researchers at the University of Minnesota adapted the data into a more user-friendly format, the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, that was used for this article.

Similar data for 2009 will be available in February, according to the Census Bureau's data-release schedule.