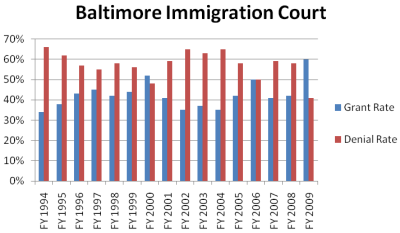

Chart depicts asylum grant and denial rates for the Baltimore Immigration Court from 1994 through 2009.

WASHINGTON (December 15, 2010) — Madjaka Berthe was restless after spending most of the day in the Baltimore Immigration Court awaiting the final hearing for her asylum request to stay in the United States, where she has lived for 13 years.

A judge was supposed to send a written decision to Berthe in August, but she was told she had to appear in court this November morning. "It's annoying."

But the 36-year-old Greenbelt woman hopes it's worth it. She can't go back to the Ivory Coast, where she was tortured based on her gender and was beaten daily for "trying to break tradition," she said, by not marrying her cousin. And she didn't apply earlier out of fear she'd be taken away from her husband and three young children, all U.S. citizens. Now, she's tired of living in uncertainty and wants to move forward.

Berthe is in the right place. Although problems pervade both the country's immigration court system and individual courts, the Baltimore Immigration Court is generally considered one of the nation's best, and with a 60.1 percent asylum approval rate the odds are in her favor.

The Princeton, N.J., based Political Asylum Research and Documentation Service rates the Baltimore court at the top of its list, based on court decisions and attorney feedback. The organization recommends that immigrants take their cases through the Baltimore court if possible, citing the judges' knowledge of immigration law and conduct.

For the first time, the Justice Department's Executive Office for Immigration Review, which oversees more than 55 immigration courts across the country, posted the total number of complaints against its judges on its website for fiscal year 2010. But the statistics aren't listed by individual judge or even by immigration court because of "privacy concerns specific to employee discipline issues," EOIR said in a statement.

Immigration attorney Cynthia B. Rosenberg has practiced before immigration courts across the country, including in Philadelphia, Chicago and Harlingen, Texas. And she doesn't have much to complain about concerning the Baltimore court.

"I think the Baltimore court is one of the best ones," Rosenberg said. "There are some immigration judges who scream at the lawyers and are nasty and insulting. I've not had that problem at Baltimore."

Rosenberg particularly likes Judge John F. Gossart Jr., one of the most senior immigration judges in the country.

"I think he sets the tempo for the judges in Baltimore," Rosenberg said.

Rosenberg also praised the variety exemplified by Gossart and the four other judges of the Baltimore court—Elizabeth A. Kessler, Lisa Dornell, Phillip T. Williams and David Crosland.

"We have male, female, black, white," Rosenberg said. "We have good diversity in our judges."

"Based on what I hear and read about other courts, there are judges that are unfair or arbitrary and unpredictable," said Patricia Chiriboga-Roby, an immigration attorney at World Relief Baltimore Immigration Legal Clinic.

Immigration lawyer Ana Zigel, a U.S. citizen who came to the country as a child from Argentina, agreed that this is not true for the Baltimore court.

"I think our judges are fair and I don't think you could ask for more than that," Zigel said. "That doesn't mean cases always go our way, because they don't."

Immigration judges, including those in Baltimore, do what they can with the few resources available to them, said Dana Leigh Marks, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges.

For example, the average federal District Court judge has 400 pending cases and three full-time attorney clerks, Marks said. But the average immigration judge has 1,200 pending cases and "one-fourth of a clerk," she said.

Judges need more resources to do their jobs as effectively as possible, especially for asylum requests, Marks said.

"Asylum cases are potentially death penalty cases that we are handling in a traffic court setting," Marks said. "The Baltimore court is an outstanding example of the court operating the best it can with the current scarce resources available to all immigration courts."

The Baltimore judges take their jobs seriously, said Maureen Sweeney, visiting assistant professor at the University of Maryland's law school and director of the school's Immigration Clinic. She's practiced in the Baltimore court since 1996.

"Unfortunately, you can't assume that in every court around the country, but that is the norm in Baltimore," she said.

But as celebrated as the Baltimore Immigration Court is, it is not immune to the widespread problems that plague the court system, such as immigrants' lack of representation, work permit delays and heavy case backlogs.

"I feel you can expect certain things with certain judges and other things with other judges," Sweeney said. But there are "no gross disparities that you find in other courts."

For example, judges' asylum denial rates in the Philadelphia court ranged from 88.9 percent to 19.2 percent in fiscal years 2001-2006, according to Syracuse University's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. Baltimore judges' asylum denial rates, on the other hand, ranged from 63.2 percent to 38 percent.

Asylum cases are one of the most common types. Each case is unique and must be judged based on its merits, so statistical analysis doesn't tell the whole story, according to EOIR.

However, the relative closeness of the Baltimore court's grant and denial rates are two indicators of its evenhandedness.

TRAC found that immigrants with lawyers fare much better than ones without lawyers, which leads to another problem with the Baltimore court, Sweeney said.

While the Arlington Immigration Court encourages lawyers to take some pro bono cases, the Baltimore court doesn't screen detainees to see if they need representation, she said.

Getting work permits is a challenge for asylum seekers, even if they do have lawyers, Sweeney said.

After filing for asylum, they have to wait 180 days to get a work permit. In the Baltimore court, any delay in an immigrant's case, even if it is out of the person's control, stops the clock, Sweeney said. Immigrants then have to wait until their case is decided to get a permit, which could take months or years.

"The law allows (Baltimore judges) to interpret it more generously than they do," Sweeney said. "That's the way they've been interpreting it, but other courts interpret it differently."

Immigrants need a way to support themselves, so the Baltimore court should make work permits more readily available, Sweeney said.

The judges also face a "truly inhuman" workload and the current emphasis on deportations intensifies the problem, she said.

"There's a huge push to deport people," Sweeney said, "so the judges are the ones who have to deal with it."

When former Baltimore Judge Jill H. Dufrense went on temporary assignment at the Falls Church, Va., immigration court headquarters, many of her cases in Baltimore were left in limbo, adding to the court's backlog. The Executive Office for Immigration Review eventually assigned a substitute to her cases, and then a replacement two months after Dufresne's job became permanent in late August.

Although most immigrants want their cases decided quickly, some welcome backlogs, because they know they will be deported and want to stay in the country as long as possible before being ordered to leave, said immigration attorney Adam Edward Rothwell.

But that's not the case for Madjaka Berthe, who left the Baltimore Immigration Court that afternoon with a future as uncertain as when she arrived. After waiting for hours, she learned of a miscommunication between the court and her lawyer. The judge had decided once again to send her a written decision to her asylum request.

"The more she postpones the decision, the more anxious I become," Berthe said. "I can't think about anything else."