This is one in a series of eight articles about the Baltimore Orioles and Camden Yards.

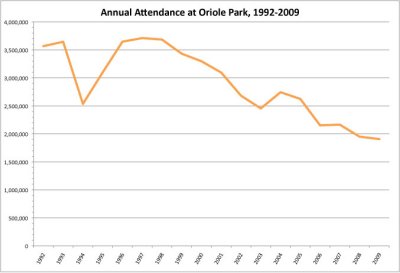

Data used in this chart was provided by the Orioles. Attendance in the 1994 and 1995 seasons was low because of the baseball strike. (Graphic by Steve Kilar)

BALTIMORE (Sept. 7, 2010)—Eighteen years after Oriole Park at Camden Yards opened in Baltimore to universal praise—and seasons of sold-out games—baseball fans continue to visit the brick-and-steel park that is often credited with rejuvenating ballpark design.

So is it a success? That depends on who's defining success.

Former state Sen. Julian L. "Jack" Lapides, a Baltimore Democrat, is one of the Marylanders who from the start opposed using taxpayers' money to build the stadium. He calls the deal with the Orioles "lousy."

But Herb Belgrad, who was chairman of the Maryland Stadium Authority when the stadium was built, notes that its purpose was never to create revenue for the state.

"This was not a fiscal project," Belgrad said. "It was to benefit the citizens."

Every year, win or lose, the Orioles pay several million dollars in rent to the Maryland Stadium Authority, the state agency that built and owns Oriole Park.

The formula for the 30-year lease, signed in 1992, is complicated. It was based on a review of ballpark leases from across the country and was intended to produce a rent figure that was a "fair median" among other baseball stadium leases, said Alison Asti, executive director of the stadium authority from 2004 to 2007.

Rent for the park equals 7 percent of net admissions revenues plus $5,000 for each special game—postseason, All-Star or exhibition games—played at Camden Yards. On top of this base is added: less than 10 percent of concessions, 50 percent of the Orioles' parking receipts, 25 percent of the advertising revenues and 7-to-10 percent of suite and club-level admissions.

From 1992 through 2009, the Orioles' average rent was about $4.5 million. Because ticket prices have gone up, rent figures have not fluctuated substantially over the past two decades—despite the fact that attendance has plunged, said David Raith, chief financial officer for the stadium authority.

The stadium authority also receives 80 percent of a 10 percent state admissions tax. From 1993 through 2010, this payment averaged about $4.2 million.

These two payment pools from the Orioles amount to about $8.7 million per year.

The state's income from the Orioles is not likely to increase substantially over the course of the 30-year lease because the state cannot effectively raise taxes on the Orioles: Any tax increase is offset in the stadium lease by a decrease in rent.

Most of this money goes toward paying the debt on the state-constructed stadium, which cost about $110 million to build, Asti said.

The rest is funneled to park maintenance, which—just as with an apartment building—is paid by the landlord.

As the stadium ages, maintenance costs increase and repair bills demand a larger portion of the stadium authority's revenue from the Orioles, Asti said.

Baltimore, struggling through the recession, gets even less from the Orioles than the state: on average, about $40,000 a year in direct net tax revenue—after subtracting the city's $1 million annual payment toward the stadium debt, according to a comparison of 18 years of accounting records from the Maryland Stadium Authority and the Maryland comptroller.

The Orioles, a private company, would not release their revenue figures.

Other park revenue feathers the team's nest: 50 percent of parking, 90 plus percent of concessions and more than 80 percent of admissions revenues. The team also gets 75 percent of traditional advertising revenue and 100 percent of "virtual" advertising revenue—the computer-generated ads that appear only on television but look as if they're mounted on the walls inside the stadium, Asti said.

To opponents of state spending on the stadium, the deal was always weighted too heavily in the Orioles' favor.

But in 1987, when the Maryland Legislature approved state funds for a new stadium in downtown Baltimore, Gov. William Donald Schaefer and city leaders presented the project as almost an emergency measure.

Late 1980s Baltimore was a city making progress—Harborplace was drawing crowds—but still plagued with drug abuse, unemployment, crime and a declining population.

And the city's football team, the Colts, had fled in the night for Indianapolis in 1984—leaving fans distraught and City Hall shaken.

Edward Bennett Williams, the Washington lawyer who owned the Orioles, was fighting cancer. He refused to sign anything longer than a one-year lease at Memorial Stadium, where the Orioles played. And he said the team would be sold at his death.

The Colts and the Orioles, like many professional football and baseball teams across the nation in the 1970s and '80s, shared a field: Memorial Stadium, a city-owned, 54,000-seat, 35-year-old structure between 33rd and 36th streets, nestled into the neighborhoods of Ednor Gardens and Waverly.

"As a result of there being a single stadium, we lost the Colts. It was the city's inability to accommodate both teams" that caused the Colts to leave, said Belgrad, chairman of the stadium authority from 1986 until 1995.

The emotional response to the loss of the Colts among Baltimore's citizens, and its elected representatives, was a driving force behind the Camden Yards project.

"People were apoplectic that the Orioles were going to leave too," said Lapides, a main opponent of the Camden Yards complex in the legislature.

Baltimore alone did not have the financial power to build a new stadium for the Orioles, said Baltimore City Councilwoman Mary Pat Clarke, who represented the neighborhoods near Memorial Stadium.

The State of Maryland, however, could finance the project. And Schaefer, who was mayor of Baltimore when the Colts had left three years earlier, was determined not to lose the Orioles as well. Backed by many of Baltimore's political and business leaders, he decided it was necessary to build the team a new stadium.

The plan was not universally embraced: "A local anesthetic for the populace" was how one Baltimore resident described the stadium bills passed by the Maryland Legislature in 1987 in a write-in forum in The Baltimore Sun.

But despite the debate, the stadium bills passed easily. They authorized the construction of Oriole Park at Camden Yards and a future NFL stadium, in addition to creating a state agency, the Maryland Stadium Authority, which would oversee the construction and management of these stadiums.

The stadium authority entered into a formal agreement with the Orioles for the construction of a new stadium and, once the stadium was complete in 1992, the team signed a 30-year lease on the park.

"One of the purposes was to make (the lease) ironclad that for 30 years we would have a baseball team here (in Baltimore)," Belgrad said. "What happened with the Colts would not happen with the Orioles."

A large part of the funding for Camden Yards came from instant lottery ticket revenue, a politically savvy idea that quelled much opposition to public funding of a stadium complex, said Delegate Samuel I. "Sandy" Rosenberg, one of Baltimore's representatives in Annapolis—and an Orioles season-ticket holder.

So Baltimore's reputation as a major league city was saved. Some economists projected spin-off financial benefits: fans spending money at restaurants, bars and hotels on game days. But that does not change the fact that Maryland and Baltimore make little direct income from the Orioles' presence.

All these years later, some opponents of the state-financed project still object.

"We did get a lousy deal," said Lapides, who filibustered the bills that allowed for the construction of Oriole Park and thinks Baltimore should receive a larger direct economic benefit from the stadium. "The city really got very little out of it."

"I think it's great the city has a team," Lapides said. "I just wish the team paid their full freight."

But no major league baseball team covers the complete costs of building and operating a stadium.

Belgrad does not see any reason the city should make money directly from the Orioles because Baltimore did not fund the stadium's construction.

"All of the funding came from (state) legislation. The city was not generating the funding for the construction," said Belgrad.

When drafting the lease, the stadium authority assumed that Baltimore's economic boost would come from increased tax revenues—particularly taxes on hotel rooms, Asti said.

"The objective was that we wouldn't lose any money and (the lease payments) would help the state pay down the debt," Belgrad said. Covering the state's debt service on the cost of the project was the stadium authority's priority, not creating income for the state or Baltimore.

Nevertheless, Baltimore has such a small amount of money coming into city coffers from Orioles' admissions taxes relative to the city's other sources of income that the city's chief of revenue collections, Henry Raymond, said he was not even aware the city made money directly from the Orioles.

The state collects admission and amusement tax revenue and distributes it to the city in a lump sum, making the Orioles' revenue a drop in the accounting bucket.

In fact, arcade games create 30 times more direct tax revenue for the city on average than the net direct tax revenue paid to the city by the Orioles.

Baltimore receives an average of $1,239,350 in tax dollars annually from "coin-operated amusement devices," according to records for 1996 to 2010 maintained by Maryland Comptroller Peter Franchot.

In contrast, the city collects an average of $1,038,681 in admission tax revenue from the baseball team per year as calculated from Maryland Stadium Authority records for 1993 to 2010. (Baltimore also receives a reimbursement from the team for city police who work inside Oriole Park, said Edward J. Gallagher, Baltimore's director of finance.)

However, the city pays out $1 million per year toward the debt on Oriole Park, as required by Maryland law, and will continue to do so through the end of the stadium lease in 2021.

Once the $1 million is subtracted from the admission tax revenue, the city nets an average of $38,681 a year from the Orioles.

In 2007 and 2009, the city paid out more toward the stadium debt than it made in admission tax revenue. This year's numbers are on track to a loss for Baltimore as well.

The $1 million annual city contribution came as a surprise in Annapolis.

In March 1987, Clarence H. "Du" Burns, who was Baltimore's mayor for less than a year, appeared before the legislature to testify in favor of the bills that would authorize the creation of the stadium authority.

Some skeptical legislators, who were concerned about the state financing a public works project that they argued would mainly benefit Baltimore, demanded to know what contributions Baltimore was going to make toward the stadium.

Burns, who died in 2003, told the lawmakers that the city would improve utilities and roads around Camden Yards—and contribute $1 million a year for 30 years toward construction costs.

This was the first anyone had heard of Baltimore's $30 million commitment to the stadium, said William B. Marker, a Baltimore lawyer and community activist who sued unsuccessfully for a referendum on the stadium bills.

Alan Rifkin, who was Schaefer's chief legislative officer and counsel when the stadium bills were being considered, met with Burns around the time of the legislative testimony. The mayor, Rifkin said, thought a city financial contribution was appropriate because the city was going to be the principal economic beneficiary.

"The city was the beneficiary of the economic value of the site location," Rifkin said.

Belgrad and Asti agree that new economic development downtown and increased traffic around the stadium—not direct tax revenue—was the financial boost Baltimore received by building Oriole Park in the Inner Harbor. Their position is supported by some academic research.

"Ballparks move tax dollars," said University of Michigan professor Mark Rosentraub, who researches professional sports' influence on cities.

Rosentraub has no doubt that building Oriole Park downtown has brought significant economic benefit to Baltimore relative to the investment the city made in building the stadium.

Oriole Park was built near Harborplace, which had been opened for more than 10 years, and the National Aquarium in Baltimore, which also was a downtown fixture.

Rosentraub said the stadium gave the area another boost. "When you look at what Baltimore looked like before (the Camden Yards stadium development) began, you have to make the conclusion that it is a great success."

According to the Orioles and the Stadium Authority, the location of the stadium downtown has been a boon to Baltimore's economy.

"The economic impact the Orioles have on the community is extremely significant and a large percentage of fans come from out of town to spend their dollars in the city at area restaurants, hotels, businesses and attractions," said Greg Bader, a spokesman for the Orioles.

The Orioles' assertion is supported by a 2006 study published by the Stadium Authority that estimated Oriole Park at Camden Yards produced approximately $7.5 million in local taxes—including income, amusement, parking and hotel taxes—for that year.

But some still believe the city has been shortchanged.

Marker, who would have preferred a renovation of Memorial Stadium, says that the money spent on the Camden Yards complex could have been put to better use.

"What if that money had been spent on schools and drug treatment?" Marker said. "Who knows what would have been."

This story was produced by the Baltimore Urban Affairs Reporting class of the Philip Merrill College of Journalism, the University of Maryland, College Park. The class is supported by the Abell Foundation, with other resources provided by The Baltimore Sun. It is distributed by the University of Maryland's Capital News Service.